By Alessa Wylie

Charles Quincy Clapp might just be one of Portland’s most famous 19th century architects that you’ve probably never heard of. He was described as “A man who took much interest in architecture and had a correct taste” and who happened to build some of Portland’s most interesting buildings.

Charles Quincy Clapp was born in Portland in May of 1799, the elder son of a prosperous Revolutionary War veteran and merchant, Asa Clapp and Elizabeth Wendell Quincy Clapp. Asa made his fortune as a shipowner, while also investing in banking and in real estate. Elizabeth was from the wealthy Quincy family of Boston. When Asa he died in 1848 he left an estate worth over $130,000.

Charles Quincy, or CQ, grew up in privilege however, not a lot is known about his early life or schooling although he probably attended Portland Academy. It is also not known where he developed his interest in architecture, but it is likely he learned it via builder’s guides and plan books. He must have had quite the collection since, in later years he donated copies of his books to the Maine Charitable Mechanics Association.

Octavia Clapp

In the early 1820s, CQ married Julia Octavia Wingate, the granddaughter of General Henry Dearborn who served on Washington’s staff during the American Revolution. As a wedding present CQ’s father Asa gave the couple the former Hugh McLellan House at Spring and High Streets, today part of the Portland Museum of Art. In 1817 Asa had purchased the property for just $4,050 after McLellan, owner of Maine’s largest shipping fleet and founder of Maine’s first bank and insurance company, had his fortune wiped out by the Embargo Act of 1807 and then the War of 1812. McLellan had built the house in 1800 at a cost of $20,000 so Asa got quite the bargain.

Shortly after moving in CQ set about “modernizing” the Federal style McClellan House by lengthening the windows on the first floor and adding some Greek Revival touches on the interior. Was this the first small step in his career as a “gentleman architect?”

The first building attributed to CQ is the flatiron Hay Building at the corner of Congress and Free Streets. Constructed in 1826, it made good use of a narrow triangle of property and featured a row of handsome arched windows on its Congress Street facade. Originally two stories in height, the third story was added on by John Calvin Stevens in 1922.

Hay Building

Next, CQ began his interest in hotels. The Portland Exchange Coffee House was built in 1828 at the corner of Fore and Market Streets. It was described as a brick structure four stories high on Fore Street but only three stories at the Market Street entrance. It had shops on the first floor, including bar and a hotel in the upper floors. When it opened on January 1, 1829 the Eastern Argus newspaper reported that “not a murmur of dissatisfaction” was heard about the structure. The building, along with several others owned by the Clapp family, was lost in the Great Fire of 1866.

Just as CQ was finishing his work on the Coffee House, he began to plan a house for his family. He sold the McLellan House to his father-in-law and built his house right next door. It was not like any residence which Portland had seen before with its temple-like facade that was designed in the Greek Revival style that was popular in the United States at the time. A comparison of the McLellan House and this house shows the changes in architecture that had happened over a 30-year period.

The house was well-received by Portland residents and visitors alike. Thirteen-year-old Samuel Longfellow, younger brother of Henry Wadsworth wrote in his diary on January 2, 1833, that he “went to Mr. Clapp’s house on Spring Street. It is a very handsome house inside. The doors are of mahogany with glass handles, and three of the fireplaces are of handsome marble.” Later that year The Portland Advertiser published the remarks of an anonymous writer who commented that the house “presents a beautiful appearance. If situated at the termination of a wooded avenue, and surrounded by ornamental trees, it would be equal in point of beauty, to any mansion I know of in New England.” CQ & Julia lived in their new house only a few years. In 1837 they returned to the larger McLellan House next door to live with Julia’s widowed mother. They did not move again.

An interesting side note about the Clapp House: the house was owned by Augustus E. Stevens who was Portland’s mayor during the Great Fire of 1866. Over 1,500 buildings were destroyed in the fire, including City Hall and in the aftermath of the fire bank and city records were stored in the house. It is also likely that city business was conducted in the house. It is now owned by the Portland Museum of Art.

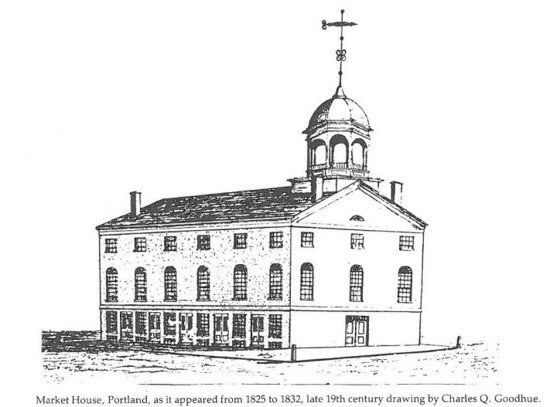

While CQ was building his own house, he was commissioned to redesign Portland’s seven-year-old Market Square/City Hall. Portland had just become Maine’s first city and it was felt that the late Federal style building needed an update so CQ offered his services. He had the cupola removed and made other changes to give it a more “modern” Greek Revival style appearance. Viewers agreed that the new facade was most elegant, but the city council found Clapp had spent much more than was expected and they debated long and bitterly before voting to pay the bills. The cupola that was removed ended up on one of the original buildings of the Westbrook Seminary which is now the University of New England and is still there today.

Market Square/City Hall before….

…and after Clapp’s redesign.

In 1836 CQ and Asa Clapp were among the incorporators of the Cumberland House, "a hotel—not a tavern” to be created by integrating several older buildings at Congress and Federal Streets to make a respectable and attractive establishment. It stood five stories tall and had 18 parlors and 57 bedrooms. Accommodations for men were offered in the Eastern Wing while the "tastefully prepared" rooms of the West Wing were reserved for women and families. It was considered to be a truly "magnificent hotel."

In 1900, the United States Hotel closed its doors and the wholesale/retail sporting goods dealer Edwards and Walker Company moved in. The building stood, with various modifications, until 1965.

Clapp’s Salem and Brackett Street duplex

In his role as a real estate developer, CQ found a way to help both his personal fortune and the City of Portland to grow. In the commercial districts he built stores and hotels while in residential areas he built houses. In 1831, speaking to the Maine Charitable Mechanic Association, CQ insisted “that though every mechanic could not have a splendid mansion, he might at least have a neat one.” After building his own “mansion” on Spring Street he adapted his ideas to smaller residences, giving each character without the cost of splendor. Examples of these include a small wooden duplex built at the corner of Salem and Brackett Streets in 1836, a block of three row houses erected on Park Street in 1846, and a large brick duplex at 126 Danforth Street.

Clapp’s “mustache” houses

More sutied to “mechanics” was Park Place, a series of ten smaller row homes built in 1848 with their own court opening off Park Street nearer the harbor affectionately call the Mustache Houses because of the wonderful decorative iron pieces above the windows. The buildings were advertised as seven-room units to be heated by stoves, not fireplaces, though they had decorative mantels.

However, not everything that CQ built at this time was scaled down. On Park Street, adjacent to the Victoria Mansion was the home of CQ’s daughter Julia and her husband John Carroll. CQ gave Julia the property in 1851 and is assumed to have designed the brick house, which, in keeping with changing styles, was Italianate in its external details though the interior reflected a transitional period with Greek Revival woodwork next to Italianate styled marble mantels in the parlor.

Around this time CQ also took part in a more ambitious enterprise. In 1850 CQ and eight others undertook to develop part of Back Cove, proposing to construct a bridge with a dam and locks at the entrance, to excavate a basin and to fit it with wharves. Although the plan was not completed, about eleven acres of Back Cove did get filled in, producing both residential and commercial land popularly referred to as Clapp’s Dump.

Middle Street after the Great Fire

The Great Fire of 1866 totally changed Portland overnight. On July 4, 1866, a fire started down on the waterfront and quickly spread through Portland destroying over 1, 500 buildings and leaving over 10,000 people homeless. CQ lost fourteen buildings and while no longer young or in good health, he went to work to replace most of them. By October 13th, he had eleven brick buildings under construction, with five already roofed in and the other six built at least up to their second stories.

CQ’s post fire buildings were constructed in the Italianate style, although two buildings, 373 Fore Street (Bull Feeney’s) and 103-107 Exchange Street, have second-story Gothic windows. And, CQ wasn’t just rebuilding for himself. On Market Street he built two structures, one for him and one next door for his son-in-law John Carroll. On Middle Street he built a building for his brother A.W. Clapp.

373 Fore Street (now Bull Feeney’s)

When Charles Quincy Clapp died in 1868, he had been associated with more than 600 recorded property transactions. Portland newspapers praised his contributions to the city, noting that “Possessing an unusual taste for architecture, in which he was excelled by few, every building erected under his auspices was designed and modelled by himself…” The papers went on to claim that “he has erected, probably a greater number of buildings on his own account than any other person.” His obituary further stated that “Though possessing a large estate he was unostentatious in his bearing; though his charities were never paraded in the press he always remembered the poor and the humblest of our population often in him found a warm and generous friend.”

NOTE: The primary source of biographical information for this article is from Joyce Bibber’s bio of Charles Quincy available at the Maine Historic Preservation’s website. The source for many of the photos is the Maine Historical Society and the Maine Memory Network.