by Julie Larry and Evan Brisentine

Bayside is full of some of the earliest homes in Portland, as they escaped the Great Fire of 1866. While other Portland neighborhoods lost most of their Federal and Greek Revival architecture during the Great Fire, Bayside suffered less damage with most of western Bayside left untouched by the flames. Some of the earliest homes on Portland’s peninsula are still standing in Bayside.

During the mid 20th century’s urban renewal period, Portland’s newly created Slum Clearance and Redevelopment Authority highlighted Bayside as a target neighborhood. In 1958 the Authority demolished 92 dwellings and 27 small businesses in what we now call East Bayside. Another 54 dwelling units were razed for the Bayside Park urban renewal project, an area that now includes Fox Field and Kennedy Park public housing. The razing of Franklin Street began in 1967 when a 100 structures were demolished and an unknown number of families relocated or were displaced.

The City’s urban renewal projects had a great effect on immigrant communities in Bayside including Italian-American, Armenian-American, and Jewish families that had settled in Portland from Eastern Europe. However many Armenian families remained in Bayside after Urban Renewal, but their numbers are dwindling and their homes are disappearing.

The first Armenian immigrants arrived in Maine in 1896 to escape growing persecution in Turkey. Starting in the early part of the 20th century, the Bayside neighborhood was home to an substantial Armenian community. More than 250 Armenian families settled in the neighborhood. The Armenians in Portland were a close-knit community. As their numbers grew, they established a school, stores, restaurants, a social club, and a bank.

Cedar Street, just downhill from Portland High School and uphill from the Oxford Street shelter, is home to a number of dwellings once owned by Portland’s Armenian community. Armenian families also lived on Lancaster, Alder, Oxford, and Smith Streets.

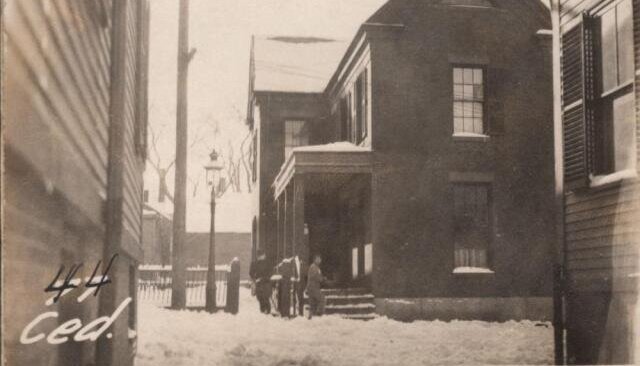

44 Cedar Street built c1855. Surrounded by parking lots, this wonderfully detailed brick building was recently for sale.

44 Cedar Street was owned for many years by members of the Tavanian [Tevanian] family (Book 1496, Page17 in 1936). Bagdasar & Gerigos Tavanian were listed as the owners in 1924 tax assessor documentation, having purchased the dwelling in 1921.

Bagdasar Tavanian (1889-1939) came to the United States in in 1906 and settled in Portland, working as a baker’s helper in a hotel at 638 Congress Street according to the 1910 US Census.

Gerigos Tavanian arrived in the United States from Turkey in 1915 according to census records. In April 24, 1915 several hundred Armenian intellectuals were rounded up, arrested and later executed at the start of a period of systematic mass murder of around one million ethnic Armenians in the Ottoman Empire during World War I. Many Armenians came to Portland 1915-1917 to escape the violence. A year before he purchased 44 Cedar Street, US Census records show Gerigos, age 24, was working as a cook and boarding with another Armenian family, the Amerigians, on Lancaster Street.

In the 1930s, 44 Cedar was owned by Louis Tevanian (36) a cook. He lived in the dwelling with his wife Rakel and their children. Rakel and Louis owned and operated a restaurant in Portland for 21 years. She also was a cashier for several years at the Pride's Corner Drive-In Movie Theater in Westbrook, a business opened by her sons John and Avadis in 1953. Also living at 44 Cedar Street in the 1930s was Robert Tevanian, a baker, and his wife Shaka and children. Until recently the dwelling was still owned by members of Shaka Tevanian’s family.

44 Cedar Street in 1924. City of Portland

44 Cedar Street was originally owned by Sarah E. Loring. She purchased the lot occupied by 44 Cedar Street in 1853. Sarah was the wife of Charles Loring, and the couple lived on the street, taking out a mortgage on their new brick house in 1855. Sarah owned the dwelling until her death in 1885. Their son George B. Loring (c1835-1896) was a founding partner of Loring, Short, & Harmon, a stationery and business supply company.

19 Cedar Street was built c1859 for Mary Jane and Peter Lane. It was demolished in August 2021.

19 Cedar Street’s earliest history shows that it was built for Mary Jane and Peter Lane in 1859. It was later owned by Sarah S. Hall, the widow of Stephen Hall, from 1867 until her death. It was purchased in the 1920s by Mesak (or Misak) Papazian 'Martin'.

19 Cedar Street in 1924. City of Portland.

Mr. Papazian (1874-1930) came to the United States in 1900 and established an Armenian grocery store. His son John Papazian Martin (1917-2010) attended nearby Portland High School and upon returning from World War II, started the 20th Century Supermarkets. John Martin built his stores into a chain of supermarkets, later known as Martin's grocery stores, that he sold to Hannaford Brothers in the early 1970's. He then began his second career in the restaurant business creating John Martin's Restaurants. John owned 19 Cedar Street following his mother's death from 1934-1944. John's daughter Andrea Martin became an Emmy and Tony Award winning actress.

15 Cedar Street was likely built prior to the Great Fire of 1866, as it had elements of Greek Revival details before the second floor was added sometime between 1924 and 1954.

15 Cedar Street in 1924. City of Portland.

15 Cedar Street’s early history is unknown, but it was probably built in the mid 19th century as it originally was a one story Greek Revival dwelling. To date in our research, Charles P. Rolfe is the first known owner of this home purchasing the dwelling c1871. He gave the property to his daughter Mary S. Deane in 1891. David W. Deane and Mary S. Deane (formerly Rolfe) married in 1861, and lived on Congress Street before owning the home on Cedar Street. David W. Deane (1838-1924) was born in Massachusetts but lived most of his life in Portland. His first career was a railroad car maker, but around 1870 became a furniture dealer. In 1879, Deane Bros. furniture store was located at 204 Franklin Street, until he added on a partner and became Deane Bros & Sandborn furniture shop and moved to 335 Congress Street. Upon Mary’s death in 1924, the property was left to David W. Deane who died later that same year.

In 1930, the property was owned by Arshag Kochian and his wife Bazza (often spelled Bazzar). Arshag and Bazza were Armenian immigrants who came to the U.S. in 1913 and 1920, respectively. Arshag worked as a laborer at a nearby pottery, possibly Winslow Pottery. In 1930s the dwelling’s second unit was occupied by the Litrocrapes family. The Litrocrapes family included Charles, his wife Helen, son George, daughter Evelyn, and Charles’ brother Lausarus. Charles (1897-1976) came to the United States from Greece in 1911 and became a citizen in 1918. His first job was a bootblack at a shoe parlor.

The Boys and Girls Club of Southern Maine bought the properties located at 15 and 19 Cedar Street behind their Cumberland Avenue clubhouse. The Boys and Girls Club of Southern Maine has yet to announce what they would like to do with the properties, but the historic homes were demolished in early August of 2021.

These Cedar Street houses not only represent Portland’s mid-19th century architectural history as well as the history of Portland’s immigrant population. You can learn more about the history of the neighborhood on our East Bayside, West Bayside, and Portland’s Chinese Community in 1920 Walking Tours

![IMG_0592[1].JPG](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/555c99afe4b027a64d6975df/1628626368088-9RQBLVJ68H0K00AVYN0L/IMG_0592%5B1%5D.JPG)

![IMG_0609[1].JPG](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/555c99afe4b027a64d6975df/1628626016176-BE53GQT40LW14TFJMFIQ/IMG_0609%5B1%5D.JPG)