Aerial view of the Portland Museum of Art’s campus with the Payson Building at center-right and, to its left, the former Children’s Museum where the expansion plan is focused. Photo appeared in the Portland Press Herald, June 1, 2022, courtesy of the Portland Museum of Art.

On Sunday, March 19, 2023, we offered our thoughts on the Portland Museum of Art's campus expansion and unification plan in a Portland Press Herald Maine Voices column (full text below). We offer these comments in a constructive and collegial manner and look forward to being actively involved in community discussions about the future of this historic and contemporary campus.

Sarah Hansen

Executive Director

As the area’s nonprofit organization devoted to historic preservation, Greater Portland Landmarks’ mission is to ensure that Greater Portland preserves its sense of place for all and builds vibrant, sustainable neighborhoods and communities for the future. We seek to build awareness and encourage public participation in the discourse and decisions that are shaping our region. It is with this mission in mind that we offer considerations on the Portland Museum of Art’s proposal to expand and unite its campus, with special concern for its implications to the PMA’s architectural legacy.

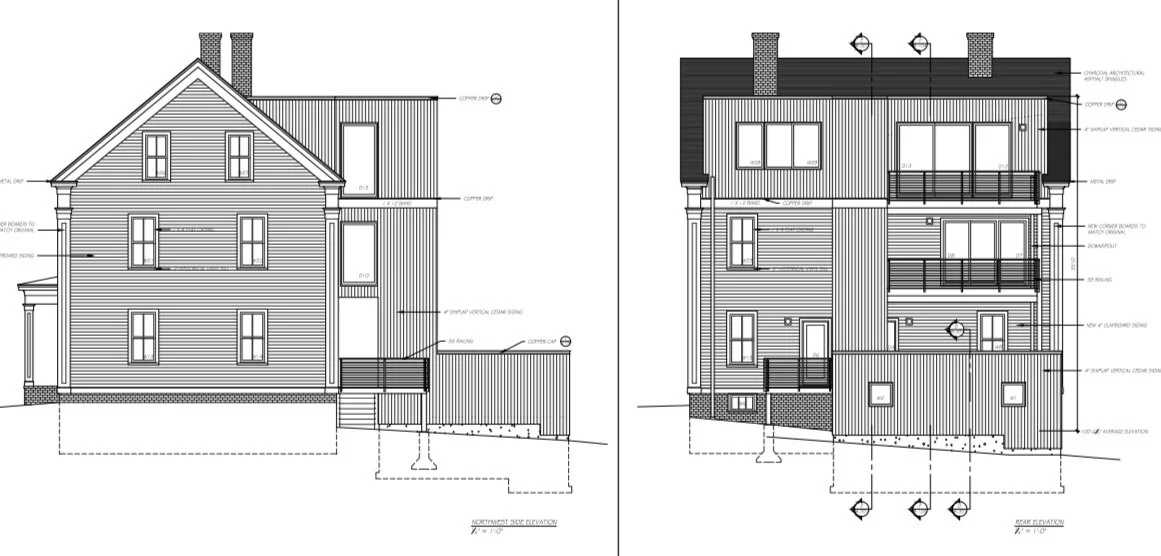

The PMA recently announced the selection of LEVER Architecture to design a major new building and master plan to unite the museum’s campus. LEVER’s initial proposal has many worthy distinctions, including its scale, choice of sustainable materials, homage to Maine’s Wabanaki heritage, and ability to welcome the public into the museum. It does not appear that the program gave significant weight to preservation considerations, including how the design should interface with existing buildings and the surrounding community.

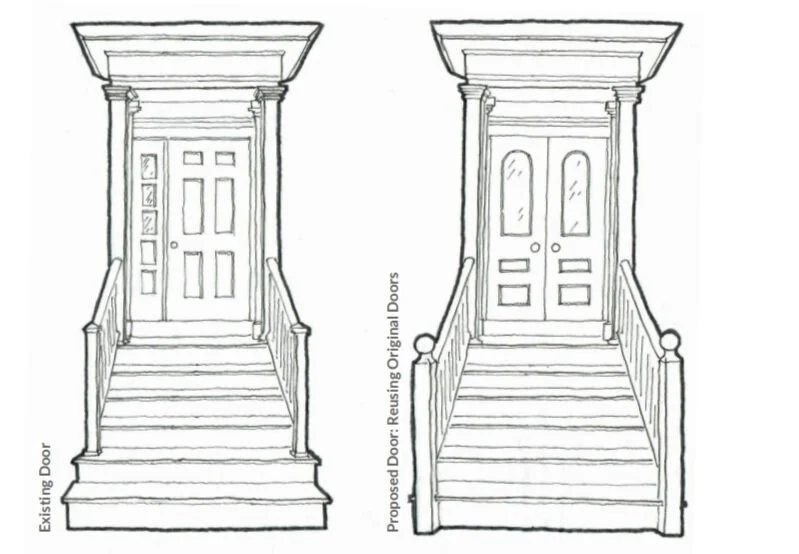

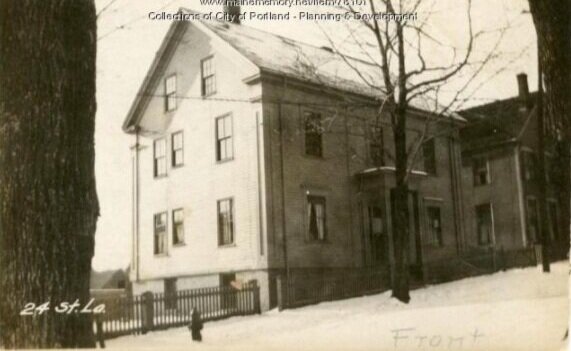

The historic buildings of the campus are a part of the PMA’s admirable “Art for All” initiative by showcasing important pieces of Portland’s architectural history. All of the campus’ buildings—including the Payson building (1983)—are contributing structures both to Portland’s local Congress Street Historic District and the Spring Street National Register District. The proposed design implicitly assumes complete demolition of one of these buildings—142 Free Street, the former Children’s Museum—without any specified justifications. Yet, the PMA will have to seek multiple City approvals to do so as 142 Free Street enjoys preservation protections against demolition or reduction to a facade based on its significance as a structure of nearly 200 years and association with notable architects, including John Calvin Stevens, a founding member of what is now the PMA.

Outside of the preservation protections for 142 Free Street (and the other buildings of the campus), the signature Payson building was designed to be in conversation with the façade of 142 Free Street, and its rhythm and scale were influenced by the earlier building. Removing that context thus diminishes the Payson building, which is also proposed to be significantly modified with the introduction of an archway leading to a High Street courtyard. This design effectively re-orients the museum away from Congress Square. These changes would dramatically affect the museum’s interactions with a major intersection undergoing significant publicly funded upgrades, including the Congress Square Park redesign. The redesigned courtyard itself has the potential to eliminate the beloved, heritage Copper Beech tree that presently graces that space.

As a major cultural institution for the city and heart of the Arts District, it is entirely appropriate for the PMA to make a bold architectural statement fitting of the twenty-first century to augment its historic campus and provide spaces for new forms of programming and exhibitions. But the PMA is also integrally stitched into the fabric of the existing city and Portland’s sense of place. As the museum looks to enhance its actions on accessibility and equity, we hope that it will also prioritize the stories that these spaces and historic structures on its campus represent—that it will use its architecture to teach us about the history and cultural heritage of the city. This is an extraordinary opportunity for the PMA to fully incorporate its architectural legacy and our shared built environment into its plans for the future.