A view of Bayside Park baseball stadium from Washington Avenue in Portland. Portland Maine History 1786 to Present

Bayside Park served as home to several independent baseball teams from its construction in 1913 up until the 1930 season. Located on the North side of Fox Street, in between Boyd and Smith Streets, it was home to not only baseball games, but to circus events and boxing matches too.

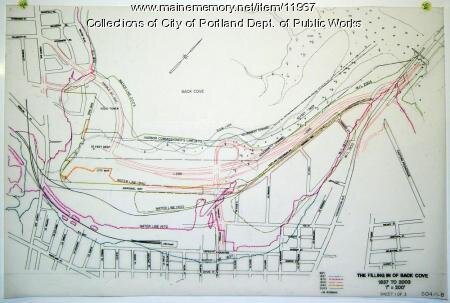

The baseball stadium was built on fill. The lower sections of what is now known as the Bayside neighborhood below Oxford Street were once part of Back Cove. Several infill projects in Back Cove took place between 1870 and the construction of I-295 over a hundred years later. Back Cove during the 1800s was full of industrial waste and residential sewage for the majority of the century. In 1895, Mayor James Baxter hired the Olmstead landscape architectural firm to improve the health and sanitation of the Cove, while also developing a scenic waterfront area for recreation. This began the development of the Portland Park System and led to the the gradual development of the Back Cove shoreline through the 20th Century.

A map depicting the various fill campaigns in the Bayside neighborhood. Portland Department of Public Works/Maine Memory Network

In 1913 when the baseball stadium was built, the shoreline of Back Cove extended to what is now Marginal Way and followed the Union Railroad tracks over the cove toward Tukey’s Bridge. The park’s Grandstands wrapped around the southern corner of the block, with Boyd Street down the 3rd base line and Fox Street down the 1st base line. An additional bleacher section was built past 1st base. If a batter really got a hold of a ball, he could make a splash hit beyond Back Cove’s high water line out in Left Field.

Bayside Park was built on Fox Street in 1913, between Boyd and Smith Streets. It’s northern boundary was the shoreline of Back Cove and the Union Railroad trestle that crossed Back Cove. Portland Public Library

The first game at Bayside Park was held on May 8, 1913. The Portland Duffs opened up their game of the new season in the New England League under legendary owner and manager Hugh Duffy. Duffy (1866-1954) was born in Rhode Island and spent most of his professional baseball career in Boston, but also played in Chicago, Milwaukee, and Philadelphia. He made his transition from playing to coaching in 1904 when he left Milwaukee to coach the Philadelphia Phillies of the National League, and then later became owner and manager of the Providence Greys of the Eastern League. After another attempt in the Major Leagues managing the Chicago White Sox, he ended up in New England as owner/manager of the newly incorporated Maine Franchise in lower Class-B New England League. Named after himself, he managed the Portland Duffs for 4 years and managed to win a pennant in 1915, but then sold the club following the 1916 season. Duffy was inducted into the Major League Baseball Hall of Fame in 1945.

Opening Day at Bayside Park in 1913. Douglas Noble/Maine Memory Network

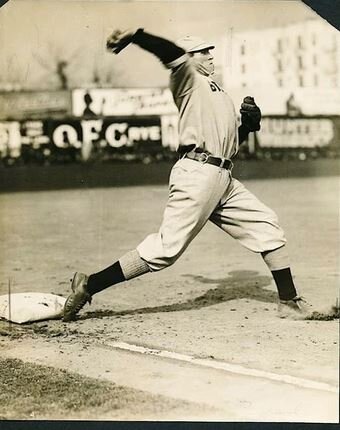

After the 1916 season a new team, the Portland Paramounts, used Bayside Park lead by manager Michael Garrity. One familiar face lasted through the team change, pitcher Fleet Mayberry (1890-1929). Earl Fleet Mayberry’s career in Portland lasted from the Duffs inaugural season in 1913 into the 1917 season with the Paramounts. After 1917 he entered the military, serving in World War I. After the war he played six more seasons of baseball and worked as a school teacher in his home state of North Carolina.

Pitching alongside Mayberry was another notable former Portland Duff player named Oscar Tuero (1898-1960). Tuero was born in Havana, Cuba and played from 1913-1941 all throughout the United States. He was with the Portland Duffs in the 1914 season, and was one of the few players from the Duffs to make it into the Major Leagues. From 1918 to 1920, Tuero pitched in 69 games for the St. Louis Cardinals.

Although the Portland Paramounts only lasted one season at Bayside Park, there continued to be a string of teams that called the park their home. The Portland Blue Sox of 1919, the Portland Green Sox in 1925, the Portland Eskimos in 1926-1927, and the Portland Mariners from 1928-1930.

Members of the Portland Green Sox at Bayside Park circa 1925. The Portland Observatory on Munjoy Hill is visible at image left above the tree line. Portland Press Herald/Maine Memory Network

Although baseball remained an extremely popular sport in Portland, the challenges of the independent baseball leagues did not allow a team to stay at Bayside Park for a long time. Teams could not constantly fill the stands and make a profit. With the construction of the Portland (now Fitzpatrick) stadium in 1930, Bayside Park was reduced to use by local Twilight and Sunset Leagues. Without a steady team occupying the park, the field and stadium were neglected, and by 1950 the grandstands were torn down.

The area of Bayside along Back Cove became an industrial area, and shortly after the tear down of the stadium in 1951, a trucking company built on top of where screaming fans previously watched baseball games. Closer to Back Cove, in what was once Left-Centerfield, was the new manufacturing building for the Songo Shoe Company. These developments would be the start to a multi-decade long change in the neighborhood along with urban renewal projects starting in the late 1950s.

Urban Renewal also gave the the neighborhood the name ‘Bayside’, when the removals made way for new developments like Kennedy Park in 1965 and the Franklin Arterial project in 1967. The urban renewal projects displaced many Irish, Italian, Scandinavian, and Armenian immigrant families who likely attended games and played in local leagues at Bayside Park. Today, Fox Field serves as a recreational grounds for sports and after school programs serving one of Portland’s most diverse neighborhoods. If you look north of Fox Street, you will see the old trucking company has become a newly renovated spot for two popular brewery restaurants. What was once the section of Smith Street connecting to Marginal Way became Diamond Street after the demolition of the Bayside Park.

The History of Baseball in Maine can draw many ties to the old site of Bayside Park. The site was at a time the outskirts of the neighborhood, but then became a front door for Portland’s after the urban renewal movement that affected so many historic homes and buildings in the Bayside neighborhood.

Some of the Portland Teams’ Members

George E "Duffy" Lewis (1888-1979) was a left fielder on three world champion Boston Red Sox teams and manager of the Portland Mariners of the New England League at Bayside Park 1927-1929. He is in the Maine Baseball Hall of Fame.

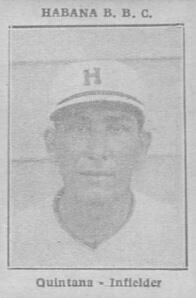

Cuban born Oscar Tuero (1893-1960) played for the Portland Duffs during the 1914 season. From 1918-1920 he played with the St. Louis Cardinals.

Roland “Cuke” Barrows (1883-1955) of Gorham, Maine was an outfielder who played Major League Baseball for the Chicago White Sox from 1909 to 1912. Although he would establish a long-time family greenhouse and floral business in Gorham, his nickname purportedly came from his “cool as a cucumber” play in tough games, not from his gardening skills. He was inducted into the Maine Baseball Hall of Fame in 1983.

James J. “Fitzy” Fitzpatrick (c1896-1989) was a teacher, athletic director and coach at Portland High School for 45 years. Portland’s Fitzpatrick Stadium is named in his honor. He also played semi-professional ball in Portland. He once faced Babe Ruth at Bayside Park in Portland, where Ruth was doing batting exhibitions. “I pitched the whole game,” Fitzpatrick recalled. “Ruth popped twice to the infield and the other two times, I struck him out, and when Babe didn’t speak to me after the game I knew he was mad and I was some shook up.” He was inducted into the Maine Baseball Hall of Fame in 1974.

Also Cuban born, Rafael Quintana played minor league baseball over six seasons with six different teams, including the 1929 season with the Portland Mariners. He also played two seasons in the Cuban leagues splitting time between Habana and Almendares.

Harry Lord (1882-1948) played four seasons at third base with the Boston Red Sox (1907-1910) and five seasons with the Chicago White Sox. Near the end of his career in 1917 he played with Portland, batting .266 in 102 games. Born in Porter Maine, he later lived in Cape Elizabeth and coached at South Portland High School. He too is in the Maine Baseball Hall of Fame.

William “Doc” Doherty was from Portland. He was a first baseman and played part of the 1929 season for Portland. He was inducted into the Maine Baseball Hall of Fame in 1972.

Frank Alexander “Pat” French was a graduate of the University of Maine at Orono who played centerfield briefly for the Philadelphia Athletics in 1917 before going off to fight later that year in World War I. He returned to Maine and would later play in 1927 for the Portland Eskimos.

Another Portlander, Ray Carr pitched for Duffy Lewis’ Portland team in 1927. Ray also pitched for Camden Club, managed by Portland’s Ray “Lanky” Jordan - a former Portland Green Sox player. Ray Jordan, as well as Ray Carr and his brother Daniel are all in the Maine Baseball Hall of Fame. Daniel worked as the grounds keeper at Bayside Park for eight years, and was a longtime Portland police officer.

Although most players at Bayside Park were men, at least one woman spent a great deal of time at the stadium. Florence Irene “Smokey” Woods caught batting practice and shagged flies for the 1913 Portland team in the New England League managed by Hugh Duffy. Known for her exceptional batting eye as well as her throwing arm, she played on several area teams. It is said that she “amazed members of Portland teams in the New England League at Bayside Park with her arm and batting skill. She was the envy of many a boy at Cathedral Grammar, where she mixed discipline with goodly doses of baseball in the schoolyard. Her baseball activities were largely confined to Portland’s Bayside Park and the local Cathedral Grammar schoolyard. She later became a nun and was known as Sister Mary Athanasia. She was inducted into the Maine Baseball Hall of Fame in 1979.

Written and researched by Evan Brisentine and Julie Larry.

Evan Brisentine was a 2021 summer intern with Greater Portland Landmarks and is currently in the Masters of Historic Preservation at the University of Oregon. He graduated from Santa Clara University with a B.A. in History and is now in his second year of his Master's program. Evan is originally from the San Francisco Bay area but experienced life in Maine when he lived in Old Orchard Beach during the summers of 2013 and 2014 playing baseball. His interests in the preservation field include cultural resource management and preservation planning.